Sunday

Chapter 1

***

The steady noise from the antique French carriage clock on the mantelpiece had somehow amplified itself, a rhythmic tick-tick, tick-tick, which usually went unnoticed. After I’d been sitting in the same position and holding my ailing mother-in-law’s hand for almost an hour, the incessant clicking had long wormed its way deep into my brain where it grated on my nerves, stirring up fantasies of hammers, bent copper coils, and shattered glass.

Nora looked considerably worse than when I’d visited her earlier this week. She was propped up in bed, surrounded by a multitude of pillows. She’d lost more weight, something her pre-illness slender physique couldn’t afford. Her bones jutted out like rocks on a cliff, turning a kiss on the cheek into an extreme sport in which you might lose an eye. The ghostly hue on her face resembled the kids who’d come dressed up as ghouls for Halloween a few days ago, emphasizing the dark circles that had transformed her eyes into mini sinkholes. It wasn’t clear how much time she had left. I was no medical professional, but we could all tell it wouldn’t be long. When she’d shared her doctor’s diagnosis with me barely three weeks ago, they’d estimated around two months, but at the rate of Nora’s decline, it wouldn’t have come as a surprise if it turned out to be a matter of days.

Ovarian cancer. As a thirty-two-year-old Englishman who wasn’t yet half Nora’s age I’d had no idea it was dubbed the silent killer but now understood why. Despite the considerable wealth and social notoriety Nora enjoyed in the upscale and picturesque town of Chelmswood on the outskirts of Boston, by the time she’d seen someone because of a bad back and they’d worked out what was going on, her vital organs were under siege. The disease was a formidable opponent, the stealthiest of snipers, destroying her from the inside out before she had any indication something was wrong.

A shame, truly, because Nora was the only one in the Ward family I actually liked. I wouldn’t have sat here this long with my arse going numb for my father-in-law’s benefit, that’s for sure. Given half the chance I’d have smothered him with a pillow while the nurse wasn’t looking. But not Nora. She was kindhearted, gentle. The type of person who quietly gave time and money to multiple causes and charities without expecting a single accolade in return. Sometimes I imagined my mother would’ve been like Nora, had she survived, and fleetingly wondered what might have become of me if she hadn’t died so young, if I’d have grown up to be a good person.

I gradually pulled my hand away from Nora’s and reached for my phone, decided on playing a game or two of backgammon until she woke up. The app had thrashed me the last three rounds and I was due, but Nora’s fingers twitched before I made my first move. I studied her brow, which seemed furrowed in pain even as she slept. Not for the first time I hoped the Grim Reaper would stake his or her claim sooner rather than later. If I were death, I’d be swift, efficient, and merciful, not prescribe a drawn-out, painful process during which body, mind, or both, wasted away. People shouldn’t be made to suffer as they died. Not all of them, anyway.

“Lucas?”

I jumped as Diane, Nora’s nurse and my neighbor, put a hand on my shoulder. She’d only left the room for a couple of minutes but always wore those soft-soled shoes when she worked, which meant I never heard her coming until she was next to me. Kind of sneaky, when I thought about it, and I decided I wouldn’t sit with my back to the door again.

As she walked past, the air filled with the distinctive medicinal scent of hand sanitizer and antiseptic. I hated that smell. Too many bad memories I couldn’t shake. Diane set a glass of water on the bedside table, checked Nora’s vitals, and turned around. Hands on hips, she peered down at me from her six-foot frame, her tight dark curls bouncing alongside her jawbone like a set of tiny corkscrews.

“You can go home now. I’ll take the evening from here.” Regardless of her amicable delivery, there was no mistaking the instruction, but she still added, “Get some rest. God knows you look like you need it.”

“Thanks a lot,” I replied with mock indignation. “You sure know how to flatter a guy.”

Diane cocked her head to one side, folded her arms, and gave me another long stare, which to anyone else would’ve been intimidating. “How long since you slept? I mean properly.”

I waved a hand. “It’s only seven o’clock.”

“Yeah, I guess given the circumstances I wouldn’t want to be home alone, either.”

I looked away. “That’s not what this is about. I’ll wait until Nora wakes up again. I want to say goodbye. You know, in case she…” My voice cracked a little on the last word and I feigned a cough as I pressed the heels of my palms over my eyes.

“She won’t,” Diane whispered. “Not tonight. Trust me. She’s not ready to go.”

I knew Diane had worked in hospice for two decades and had seen more than her fair share of people taking their last breaths. If she said Nora wouldn’t die tonight, then Nora would still be here in the morning.

“I’ll leave in a bit. After she wakes up.”

Diane let out a resigned sigh and sat down in the chair on the opposite side of the bed. A comfortable silence settled between us despite the fact we didn’t know each other very well. I’d first met Diane and her wife Karina, who were both in their forties, when they’d struck up a conversation with me and my wife Michelle as we’d moved into our house on the other side of Chelmswood almost three years prior. Something about garbage days and recycling rules, I think. The mundane discussion could’ve led to a multitude of drinks, shared meals, and the swapping of embarrassing childhood stories, except we were all what Michelle had called busy professionals with (quote) hectic work schedules that make forging new friendships difficult. My Captain Subtext translated her comment as can’t be bothered and, consequently, the four of us had never made the transition from neighbors to close friends.

Aside from the occasional holiday party invitation or looking after each other’s places whenever we were away—picking up the mail, watering the plants, that kind of thing—we only saw each other in passing. Nevertheless, Karina regularly left a Welcome Back note on our kitchen counter along with flowers from their garden and a bottle of wine. Not one to be outdone on anything, Michelle reciprocated, except she’d always chosen more elaborate bouquets and fancier booze. My wife’s silent little pissing contests, which I’d pretended to be too dense to notice, had irked me to hell and back, but when Nora fell ill and Diane had been assigned as one of her nurses, I’d been relieved it was someone I knew and trusted.

“I’m sorry this is happening to you,” Diane said, rescuing me from the spousal memories. “It’s not fair. I mean, it’s never fair, obviously, but on top of what you’re going through with Michelle. I can’t imagine. It’s so awful…”

I acknowledged the rest of the words she left hanging in the air with a nod. There was nothing left to say about my wife’s situation we hadn’t already discussed, rediscussed, dissected, reconstructed, and pulled apart all over again. We’d not solved the mystery of her whereabouts or found more clues. Nothing new, helpful or hopeful, anyway. We never would.

Silence descended upon us again, the gaudy carriage clock ticking away, reviving the images of me with hammer in hand until the doorbell masked the sound.

“I’ll go,” Diane muttered, and before I had the chance to stand, she left the room and pulled the door shut. I couldn’t help wondering if her swift departure was because she needed to escape from me, the man who’d used her supportive shoulder almost daily for the past month. I decided to tone it down a little. Nobody wanted to be around an overdramatic, constant crybaby regardless of their circumstances.

I listened for voices but couldn’t hear any despite my leaning toward the door and craning my neck. I couldn’t risk moving in case Nora woke up. Her body was failing, but her mind remained sharp as a box of tacks. She’d wonder what I was up to if she saw my ear pressed against the mahogany panel. Solid mahogany. The best money could buy thanks to the Ward family’s three-generations-old construction empire. No cheap building materials in this house, as my father-in-law had pointed out when he’d first given me the tour of the six bedrooms, four reception rooms, indoor and outdoor kitchens (never mind the abhorrent freezing Boston winters), and what could only be described as grounds because yard implied it was manageable with a push-along mower.

“Only the best for my family,” Gideon had said in his characteristic rumbly, pompous way as he’d knocked back another glass of Laphroaig, the broad East Coast accent he worked hard to hide making more of a reappearance with each gluttonous glug. “No MDF, vinyl or laminate garbage, thank you. That’s not what I’m about. Not at all.”

It’s in the houses you build for others, I’d thought as I’d grunted an inaudible reply he no doubt mistook for agreement because people rarely contradicted him. As I raised my glass of scotch, I didn’t mention the council flats I grew up in on what Gideon dismissed as the lesser side of the pond, or the multiple times Dad and I had been kicked out of our dingy digs because he couldn’t pay the rent, and we’d ended up on the streets. My childhood had been vastly different to my wife’s, and I imagined the pleasure I’d find in watching Gideon’s eyes bulge as I described the squalor I’d lived in, and he realized my background was worlds away from the shiny and elitist version I’d led everyone to believe was the truth. I pictured myself laughing as he understood his perfect daughter had married so far beneath her, she may as well have pulled me up from the dirt like a carrot, and not the expensive organic kind.

Of course, I hadn’t told him anything. I’d taken another swig of the scotch I loathed, but otherwise kept my mouth shut. As satisfying as it would’ve been, my father-in-law knowing the truth about my background had never been part of my long-term agenda. In any case, and despite Gideon’s efforts, things were working to plan. Better than. The smug bastard was dead.

And he wasn’t the only one.

***

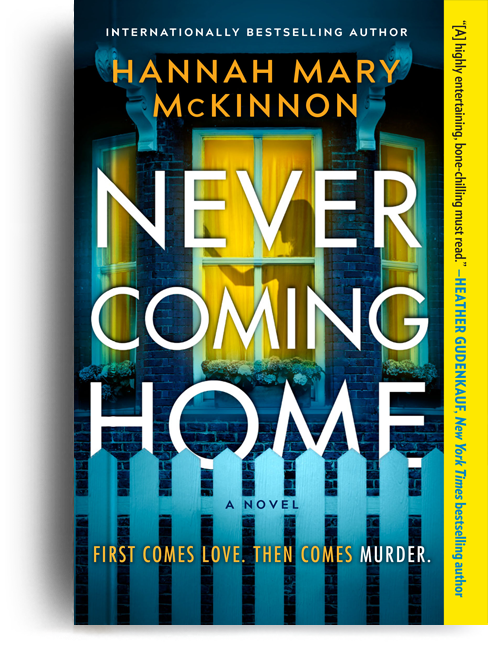

Excerpted from Never Coming Home by Hannah Mary McKinnon, Copyright © 2022 by Hannah McKinnon.

Published by MIRA Books